by Hanna Niner

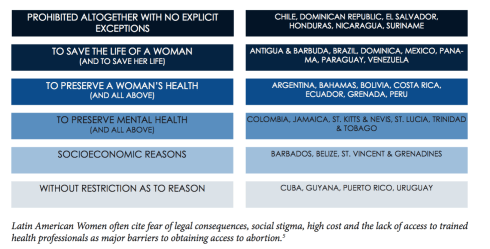

The World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 3.7 million unsafe abortions occur annually in Latin America and the Caribbean, leading to approximately 2,000 deaths—11 percent of the total maternal death rate in the region.3, 10, 12 22 percent of women have unmet reproductive health needs, with some areas having “one-third to one-half of sexually active young women” lacking access to contraceptives.14

Female citizens of Latin American countries demand that their governments legalize abortions and ensure reproductive rights in order to protect their basic human rights as females.4, 3, 10 Women are entitled to the liberty and autonomy that allows them to make sexual and reproductive decisions. In short, reproductive rights are human rights.13 The fact that women bear the sole biological responsibility for reproduction means that they face discrimination when reproductive issues, such as unsafe abortions, inhibits their ability to maintain not only their health and life itself.3, 13 Article 12 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) calls for States to “take all appropriate measures to eliminate discrimination against women in the field of health care…including those [services] related to family planning” and “services in connection with pregnancy.” Article 16 of CEDAW states that women have the right “to decide freely and responsibly on the number and spacing of their children and to have access to the information, education and means to enable them to exercise these rights.” In a region where access to contraceptives remains problematic, emergency contraceptives are severely restricted and abortion is illegal, how can the women of Latin America be empowered socially so that their health is also protected (Center for Reproductive Rights 2013)? In order to understand why women continue to lack basic reproductive rights, one must first recognize prevailing Latin American culture. Scholars demonstrate several reasons why women in Latin America face discrimination concerning their reproductive health, including: the strong anti-abortion rhetoric of the Catholic Church, the disempowerment of women in Latin America’s patriarchal society and the overall lack of education for women. For this reason, it is imperative to ask this question: Do countries with more female representatives and higher social and political empowerment among women provide better access to healthcare and reproductive rights to its female citizens?

If you like The Contemporary and want to help us empower collegiate journalists across the country, please consider donating here.

The Catholic foundation of recently democratized Latin American states creates antagonism between religion and women’s rights.3, 10 The Church dominates reproductive rights discourse by linking issues such as abortion and birth control with morality and religion.10 It opposes the legalization of abortion in any form, including in the instances of rape, incest, or risk to the mother.3 In order to combat this, individuals in favor of reproductive rights simultaneously support the separation of Church and State.10 Instead of arguing abortion from a moral or religious standpoint, individuals frame abortion as a public health and human rights issue with the framework of international law to support their advocacy.3, 10

The social disempowerment of women is the most important aspect to examine. Societies that disempower women simultaneously impede a female’s ability to claim and exercise her reproductive rights.7, 12 Women struggle to obtain reproductive rights in societies that base the value of a woman on her ability to produce children—attitudes formed through cultural and religious practices.13 The discrimination women face concerning their reproductive health remains closely linked to the prejudices and stereotypes pertaining to their “sexual and reproductive roles and functions” in patriarchal societies like Latin America. Patriarchal societies create an unequal power relationship between women and men, leading to women lacking the authority to deny sex or demand safe sex—factors that, combined with lack of access to contraceptives, lead to unwanted pregnancies.13 Also, women placed in an inferior position within society are at risk for violence. This relationship between disempowerment and an increase in gender-based violence contributes to the lack of power women hold in their sexual lives.8

When societies undervalue women and girls, they often do not receive an adequate or equal education compared to their male counterparts. Education proves an important factor in women’s reproductive lives; when education is increased, women delay marriage and the rates of adolescent pregnancy decrease.11 Around the globe, when a young woman has completed less than seven years of school, the probability of her entering into an early marriage increases.12 In Latin America specifically, girls who attend school fewer than seven years have been found to be “four to five times more likely to engage in early sex.” Taking into consideration the lack of access to contraceptives for a large quantity of young women, early marriage and early sex remain problematic in a region that does not provide support for a woman, such as emergency contraceptives or abortions, after she discovers an unwanted pregnancy. On the other hand, young women, especially those in poverty, lack access to education pertaining to their reproductive health, which further inhibits sexually active adolescents and women from making well-informed reproductive decisions.12

Limited access to reproductive education inhibits women’s informed health decisions.

Ecuador and Peru were chosen for this case study for a myriad reasons. First, the countries are located next to each other on the Northwestern coast of South America with Ecuador situated above Peru. Due to this geographic proximity, Ecuador and Peru have a similar topography, such as the Andes Mountains—a factor that can prove important in impeding the delivery of healthcare, given the difficult terrain. Second, both countries share some cultural traits, such as the machismo characteristics present in patriarchal societies and the Spanish language. Third, Ecuador and Peru have a unicameral legislative body, making the statistical comparison between these two countries easier.9 Ecuador and Peru, however, have vastly different political climates pertaining to the reproductive rights of their female citizens. Ecuador is far more developed than Peru. As Peru continues to struggle with a multitude of human rights violations and the basic issues present in developing countries, Ecuador has successfully been able to shift its focus to the complex issue of reproductive rights that more highly developed countries can allocate time and resources to address.

Ecuador has one of the most liberal reproductive rights policies in Latin America.7 In fact, Ecuador was the first Latin American country to include both sexual and reproductive rights in their 1998 Constitution, followed by the adoption of a National Policy of Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR) in 2005.7 SRHR is based on the ideals of human rights that focus on increasing women’s reproductive and sexual rights.7 In addition to SRHR, many other laws provide female citizens more rights, including Ley de Maternidad Gratuita y Atención a la infancia (LMGYAI), that provides free care to mothers and infants, along with other free services related to reproductive health, such as “contraceptive counseling, screening for cervical cancer, [and]…laboratory tests and treatment for sexually transmitted infections.” Overall, the government of Ecuador has put in place policies that provide reproductive and sexual rights to the millions of women who inhabit their country—a fact that cannot be said about many other Latin American countries.

Peru represents an overall less developed state with a maternal mortality of 362 deaths per every 100,000 births—a figure that ranks as one of the highest in Latin America and higher than the global rate of 265 deaths for every 100,000 births.12 The illegality of abortion in Peru, a country where 60 percent of pregnancies are deemed unwanted, remains a contributing factor to this staggering maternal mortality statistic.6 “For every 100 live births in Peru,” 66 pregnancies end in abortion, further exemplifying the fact that simply making abortion illegal does not stop women from deciding to abort their fetus. Instead, the laws passed by the government of Peru that make abortion illegal lead women to seek unregulated, underground abortions which translates to 30 percent of abortions resulting in unnecessary complications.6 Even though contraceptive use has increased over the past decade, 25 percent of women who are sexually active and of reproductive age do not have adequate access to contraceptives that can prevent these unwanted pregnancies.6

Although Ecuador has legal initiatives in place to protect reproductive rights and provide reproductive health care, access to services across the country remains poor; simply because a policy exists does not ensure that it is implemented effectively.7 In reality, 20 percent of pregnancies are deemed as unwanted —a number far less than the 60 percent of unwanted pregnancies in Peru.7 Even though the statistic is a third of the number of unwanted pregnancies in Peru, one must question if these women wish to obtain contraceptives to prevent pregnancy, but the government did not successfully meet their needs.7 Overall, Ecuador’s vast number of reproductive rights policies makes it one of the most liberal countries in Latin America. Even though these policies have not been fully implemented and issues pertaining to the reproductive health of female citizens remains problematic, Ecuador has the minimum legal foundation for reproductive rights in place to build upon. Yet Peru lacks the legal backing of reproductive rights that Ecuador has built into their legislation. Is this disparity due to the number of female representatives in each country?

Despite having more female representatives, Peru’s policies remained very restrictive.

It is possible that a country will have more liberal laws concerning women’s reproductive health if more women hold political office. In theory, female representatives would be more likely to support laws that increase the reproductive rights to their female constituents— allowing women to make decisions pertaining to their own reproductive health, not the government. Female representatives are already aware of many of the issues women face as a group concerning their reproductive and sexual lives. In reality, male representatives can attempt to comprehend the reproductive issues women face but fail to truly understand. This phenomenon is due to the fact that men have never been affected nor will ever have to struggle to navigate their sexual lives in a society with strict, conservative laws that govern their personal reproductive health decisions.

In actuality, the governments of Peru and Ecuador had very similar percentages of women in their Lower Houses during 2005, with Peru at 18 percent and Ecuador at 16 percent.9 Between 1991 and 2000, Ecuador and Peru were among 11 other Latin American countries that passed quota laws, in which women had to make up at least 20 to 40 percent of the candidates running for legislative offices.9 Before Ecuador passed its quota law, women composed only four percent of the legislative body. After the law, the number of women in office rose to 16 percent—a 12 percent increase.9 On the other hand, in Peru, women comprised 11 percent of its legislative body before its quota law, which rose to 18 percent after the passing of its quota law—an overall increase of 7 percent.9

Besides the number of female representatives, women in leadership move society’s direction toward the political and social empowerment of female citizens. Ecuador and Peru appear to differ in their public attitudes toward female leaders, with Ecuador having 37 percent in agreement with a statement that “‘men are better leaders than women’” while only 23 percent of Peruvians proved hostile toward female leadership.9 Overall, the general public of Peru appears to accept female representatives more than in Ecuador, which explains why Peru has more women in legislative office than Ecuador.9

If more women in office leads to more representation of female constituents and an increase in the reproductive rights of women, one might venture that Ecuador would have more female representatives than Peru, given Ecuador has more liberal reproductive policies in place and overall better health system for women than Peru. In actuality, Peru had a higher percentage of women in its unicameral legislature in 2005 than Ecuador—a contradiction between theory and the reproductive and sexual health reality of women.9 One reason why the theory of more female representatives does not necessarily mean more liberal reproductive policies can be attributed to the fact that some women in office do not support the legalization of abortion or other reproductive health issues. This theory is based on the assumption that female representatives automatically support various reproductive rights due to the fact that they are biologically female.

Although this can prove true for some women, the assumption cannot be applied to all female representatives: some might hold very conservative beliefs pertaining to reproduction. On the other hand, one could argue that the number of women in office has failed to reach the critical mass necessary to impact reproductive rights legislation. The theory of critical mass argues that women must constitute a certain percentage of the overall legislative body of a government in order to have the political power to change legislation. In the study of female representation in political office, the argument has been made that women will not gain full representation as a sector of the population until the number of representatives reaches a critical mass—Ecuador and Peru could have simply failed to reach the critical mass necessary.

Latin American governments will continue to deny their female citizens’ reproductive rights which they are entitled to as autonomous individuals, until women are empowered socially to demand these basic human rights from their governments. Although the case study disproved the theory that more female legislative representatives would lead to more liberal reproductive policies; it proved that female representatives are not absolutely necessary for reproductive rights legislative reform. Ecuador demonstrates that a country can have a small overall percentage of female representatives, but still have reproductive policies in place for its female citizens.

Even though focusing specifically on electing women into office proves important, efforts must also be spent electing individuals in general, whether male or female, that support reproductive rights. In conjunction with this shift in focus, Latin American countries have to change both socially and culturally toward placing more value on the lives of women and their reproductive health. This will prove to be a large feat in which the individuals involved must balance remaining culturally aware and sensitive while being mindful of the negative health consequences restrictive, conservative laws have on the health of Latin American women.

In order to secure reproductive rights for the millions of women across Latin America, women must first be empowered within their own communities through educational opportunities, an increased number of women in positions of legal representation, and an overall change in the machismo, patriarchal culture that permeates politics.11 Indeed, this is a large feat. When women obtain a higher educational level or position in the labor force, they desire more reproductive rights, proving that the starting point for such a complex political issue like reproductive rights begins with basic education for women.3

A government’s attempt to control women’s bodies through legislation is both ineffective and negative for women’s health; laws that prohibit abortion correlate with high rates of unsafe abortions.3, 10 International law already calls for improving the reproductive rights of females, but lacks the power to force the implementation of these policies on the sovereign states of Latin America—the movement must come from inside a country.4

The movement for reproductive rights can start by empowering women socially, giving them the power necessary to demand the protection of their reproductive health that are unique to them as women. This empowerment will stem from the general education of women and girls along with the specific education about their bodies and their legal rights—education is power. As the world continues to move into the 21st century, the global society must ensure that half of the population is not left behind in the chains of restrictive reproductive policies. C

The views expressed in this article are those of the writer, The Contemporary takes no position on matters of policy or opinion.